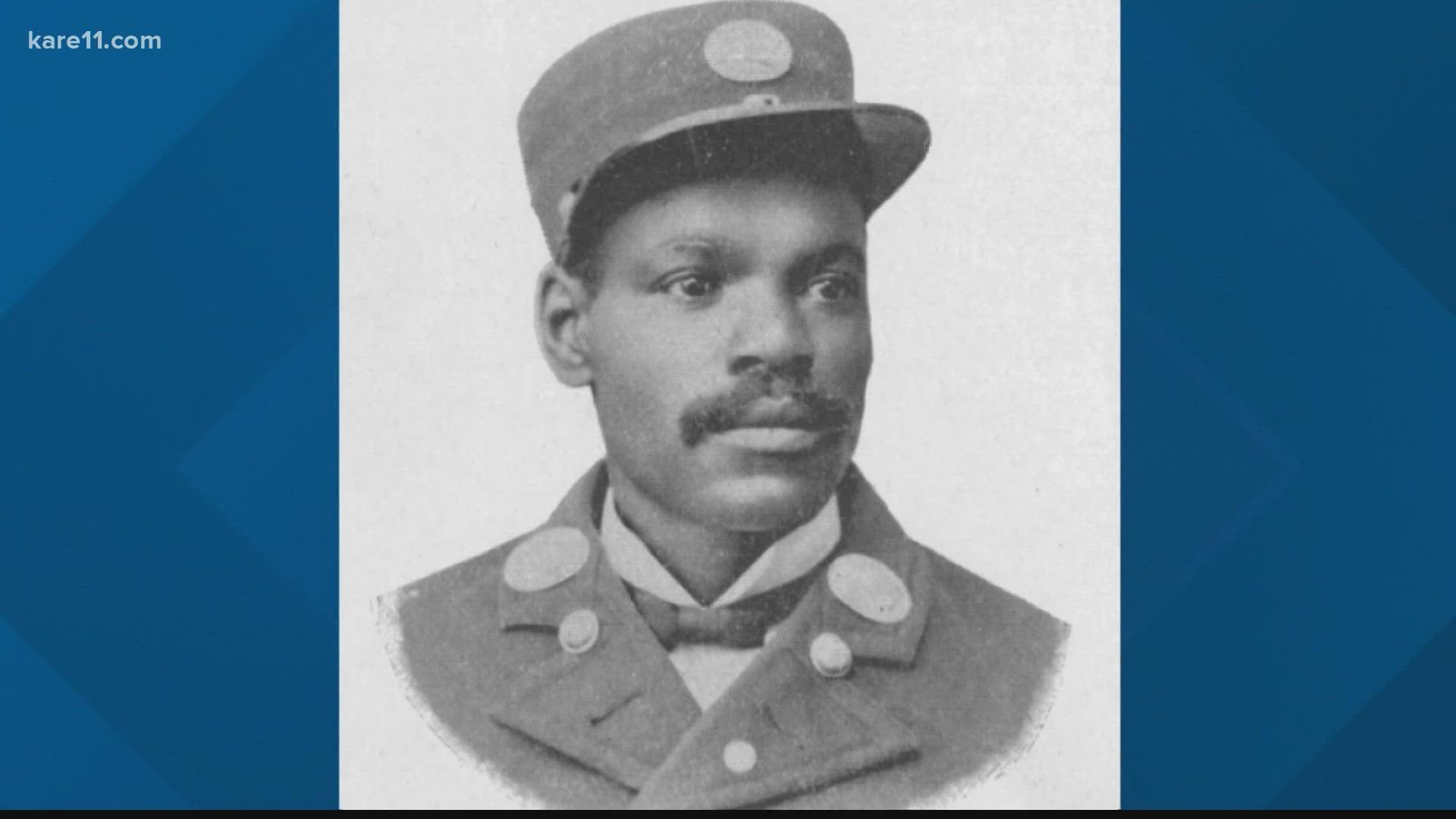

MINNEAPOLIS — Dight Avenue is a quiet city street that stretches for 10 blocks along the city's south side, running parallel to Hiawatha Avenue. Soon, the name "Dight" will be replaced with "Cheatham" in honor of the city's first Black firefighter, John Cheatham.

Cheatham was born into slavery in the state of Missouri in 1855 and came to Minnesota at the age of 8 after Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. In 1888, at the age of 33, he became a member of the Minneapolis Fire Department.

"As an adult, he worked as a laborer, as many people do. But eventually he was hired as pipeman with the fire department," Joseph Waters, a retired Maplewood firefighter and firefighting historian, told KARE 11.

"We're always honoring athletes and members of the clergy. I think it's great that we're honoring an ordinary guy who carried his lunch to work every day and just did the job to support his family."

Cheatham was promoted to lieutenant about five years into his tenure, and then promoted to the rank of captain in 1899, according to Waters. Unfortunately, he was demoted back to pipeman a year later, apparently for refusing to comply with an order from a white firefighter who held the same rank.

"Rumor has it -- and we'll leave it at that - he showed up at a fire and was given an order from another captain, and he responded, 'I only take orders from the chief.' These days you might get a reprimand, but in those days it meant a demotion to pipeman or nozzleman."

Cheatham worked at several different fire stations across the growing metropolis, eventually landing at Station 24 at 45th and Hiawatha. It was built in 1907 as the city's first all-Black firehouse. Waters and others have been busy sifting through city records, finding the names of the African American firemen who worked in Station 24.

At first there was community resistance to the notion of an all-Black crew setting up shop in Station 24, but it also garnered community support. By that time the area along the railroad lines was starting to become integrated.

The area lacked its own fire station. And there was also the practical consideration that many white firefighters at the time made it clear they didn't want to share living quarters with Black men.

When Station 24 closed in 1941, it ushered in a new era of segregation in the Minneapolis Fire Department, which didn't end until a law suit forced integration of the agency in 1971.

"They had ways of making the civil service tests impossible for people to pass if they had already decided they didn't want to hire them," Waters explained.

Several groups, including the Minneapolis African-American Professional Firefighters Association, are trying to save the Station 24 building and preserve it as an important part of Twin Cities history.

The Minneapolis Heritage Preservation Commission on Dec. 14 approved City Council Member Andrew Johnson's application to designate Station 24 as a local historic landmark.

In January, the Minneapolis City Council voting to unanimously approve the historic title.

Any building designated as a local landmark can't be demolished or significantly altered without first being reviewed by the city's Community Planning & Economic Development department and the Heritage Preservation Commission.

RELATED: 'This is a really historic moment' | Minneapolis designates all-Black fire station as a landmark

Charles F. Dight

The current namesake for Dight Avenue was a city alderman, medical doctor, university professor and strong advocate of a movement that lost favor decades ago.

Dr. Charles F. Dight led the Minnesota Eugenics Society, part of a nationwide movement that advocated the notion of creating a utopian society by eliminating genetic traits deemed to be inferior or immoral.

As recounted in an entry in the Minnesota Historical Society's Minnopedia, Dr. Dight and the Eugenics Society successfully convinced the state legislature to approved sterilization of "feeble-minded" persons at an institution in Faribault.

According to MNHS, the board that controlled and tracked the process recorded more than 2,000 sterilizations of patients, 70% of whom were women.

The MNHS collection on eugenics includes a letter Dight sent in 1933 to Adolph Hitler, thanking him for his efforts to "stamp out mental inferiority" through eugenics in Germany. The letter included a newspaper clipping of Dight's letter to the editor of the Minneapolis Journal, praising Hitler's efforts toward "social good and racial betterment."

Hitler replied to Dight with an invitation to a eugenics conference in Munich.