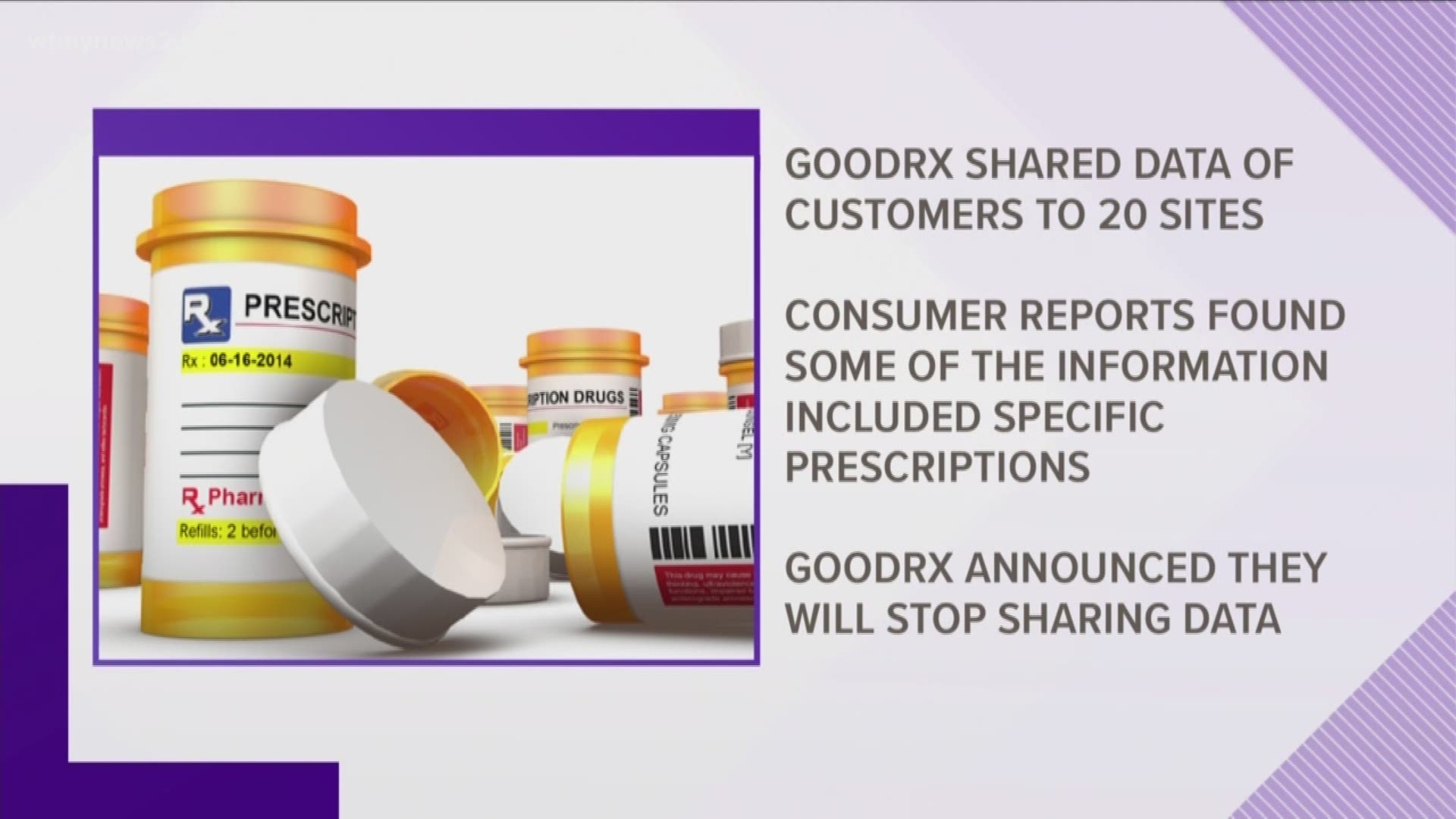

Update: After this article was published, GoodRx posted a statement saying that it planned to stop sharing personal medical information with Facebook, had appointed a new VP of data privacy, and was providing a way for GoodRx users to delete their data.

Original story: A few weeks ago, a Philadelphia resident named Marie received a prescription for a new medication, but the drug wasn’t covered by her insurance. “It was way too expensive for me to get on my own,” she says. (Like other consumers we spoke to, she asked us to withhold her last name to preserve her privacy.) “So I reached back out to my doctor. She directed me to GoodRx, and said I’d be able to afford the medicine with one of their coupons.”

The doctor was right. “The discount was about $500,” Marie says. “I was excited to go fill the prescription and not have to worry about it anymore.”

Millions of people like Marie have downloaded the GoodRx app. The price comparisons and coupons it provides can save money on prescription drugs that otherwise would be out of reach for many patients. That’s why Consumer Reports and other organizations have recommended GoodRx in the past.

However, there is a tradeoff involved.

While people like Marie are saving money with GoodRx, the company’s digital products are sending personal details about them to more than 20 other internet-based companies. Google, Facebook, and a marketing company called Braze all receive the names of medications people are researching, along with other details that could let them pinpoint whose phone or laptop is being used.

That worries patients like Marie, along with doctors and healthcare advocates we interviewed.

“It’s becoming a situation where privacy is for the privileged,” says Dena Mendelsohn, a senior policy counsel for Consumer Reports. “People use GoodRx when they’ve been prescribed something to improve their health, which in some cases can be a life-changing drug. But people shouldn’t be in a position where they have to choose which is more important, their health or their privacy.”

Medication Names Are Shared

To determine how GoodRx shares data, we monitored traffic using a data packet-capturing tool to observe the company's Android mobile app and website as we searched for deals on a number of prescription medications.

Several of the company’s business partners received the names of the medications, along with ID numbers and other information that can be used to single out individuals. The data can reveal intimate information that many people would keep private from all but their close friends and family.

As a test, we looked for discounts on Lexapro, an antidepressant; PrEP and Edurant, used to prevent and treat HIV, respectively; Cialis, for erectile dysfunction; Clomid, a medication used in fertility treatments; and Seroquel, an antipsychotic often prescribed to control schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

With the information coming off our test phone and browser, a company could infer highly intimate details about GoodRx users suffering from serious chronic conditions, and make educated guesses about their sexual orientation.

Braze, a marketing firm, received the names of the drugs, the pharmacies where we sought to fill prescriptions, and ID numbers that advertising and analytics companies use to track the behavior of specific consumers across the web.

Like other companies we talked to, Braze assures Consumer Reports that the data collected isn’t shared broadly with data brokers or advertising companies. Braze says the data is only used to help GoodRx target its own users with information.

Similarly, a company called Branch says it only uses the data it collects from GoodRx to make sure that links within the mobile app work correctly. GoodRx executives say the company doesn’t sell or share users’ health data with other companies to support targeted advertising.

“When we believe a user is running out of medication, we use Braze to email or text a reminder," says Thomas Goetz, chief of research at GoodRx. "We may also notify users when we are able to find a better price for their prescription,” he says. “To reach new customers who might find GoodRx useful, we place advertisements for GoodRx on third-party platforms, including Facebook and Google, and retarget users who have visited GoodRx to encourage them to come back and use the service.”

Both Google and Facebook deny using prescription information for targeting individuals with ads. “We prohibit personalized advertising and advertising profiles based on sensitive information, including a user’s prescriptions,” a Google spokesperson says.

A Facebook spokesperson says, “We don’t want websites sharing people’s personal health information with us—it’s a violation of our policies. After an initial review, we think GoodRx’s use of our business tools requires a deeper investigation, and we’re reaching out to the company.”

Our testing of the GoodRx app and website was led by Bill Fitzgerald, a privacy researcher in CR’s Digital Lab. “We observed sensitive information being passed along," he says. "If Facebook doesn’t want this information, and GoodRX doesn’t want to send it, it shouldn’t be happening. The app and site don’t need to be designed this way.”

GoodRx users we reached out to say they are surprised such intimate information was being shared for any purpose.

“I just assumed that there had to be some kind of protection laws or something associated with it because, you know, it’s medical data,” says Cam, a GoodRx user who works as a business analyst in New York.

“My instinct was that it was okay, probably because of my past experience with medical information,” Marie of Philadelphia says. “I just assumed, you know, this was my private prescription app."

“It doesn’t feel right,” she says.

No, HIPAA Doesn't Apply

Doctors we interviewed say they worry on a daily basis about how patients can pay for the drugs they need to treat serious medical conditions. All of them say they recommend GoodRx as a solution, many without realizing that private information could be revealed.

Erin T. Bird, M.D., a urologist in Temple, Texas, frequently brings up GoodRx to his patients. “It’s a conversation that occurs with pretty much every prescription,” Bird says, especially when he's dealing with erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, and cancer—conditions that call for medications that are expensive under many insurance plans, and potentially embarrassing for patients.

Bird says he is surprised that the GoodRx app and website share patients’ prescription information.

“I think that most physicians would think that within the space of healthcare, there are some consumer protections. I would have assumed that,” Bird says.

Bird and other medical professionals are required to keep medical information private and secure under HIPAA, or the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. You’ve probably dealt with HIPAA before—it’s described in the documents you sign when you visit a new doctor’s office.

“If people think that HIPAA protects health data, then they probably believe that any health data in any context is going to be protected. That’s just not the case,” says Deven McGraw, chief regulatory officer at consumer health tech company Ciitizen and former deputy director of health information privacy at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services' Office of Civil Rights.

However, HIPAA doesn’t apply to GoodRx or many other “direct-to-consumer” websites and apps that provide health and pharmaceutical information. It doesn’t apply to heart-rate data generated by a sports watch or Fitbit, information you enter into period-tracking apps, or running data held by running and cycling apps such as Strava. As far as the law is concerned, such information has no more protection than your Instagram likes.

Major companies are keenly interested in consumer health data. Last year, the data broker and credit monitoring agency Experian announced it had assigned every person in the United States, an estimated 328 million Americans, a unique “Universal Patient Identifier.” Google and Amazon are publicly investing in efforts to collect consumer health data and acquire or partner with healthcare companies.

HIPAA may actually make medical data more valuable to internet companies. “I can buy a targeted list of people that have opened a new business or bought a BMW,” says Jeff Greenfield, co-founder of the advertising attribution firm C3 Metrics, but it’s much harder to locate people with diabetes or high cholesterol because of HIPAA. “There’s money that's on the table, hundreds of millions, billions of dollars a year in aggregate, in potential advertising dollars.”

A 'Necessary' Tradeoff

Prescription coupon services aren’t the only apps sharing sensitive information with third parties.

A recent study by the Norwegian Consumer Council, an advocacy group, looked at 10 apps, including Grindr, OkCupid, Tinder, and the period-tracking apps Clue and MyDays, and found they were collectively feeding personal information, which for some apps may include details about users’ gender, sexuality, political views, and drug use, to scores of companies.

In January, a Gizmodo investigation found that a panic-button app partnering with Tinder shared data with many of the same companies we spotted when we looked at GoodRx. Last week, a report from Jezebel found similar data sharing in the world of online therapy services, such as BetterHelp.

GoodRx says it is careful with consumer data, and that it makes most of its revenue through referral fees collected when consumers fill prescriptions using a GoodRx coupon, rather than through advertising.

However, when you use an app, whether it’s a calculator, GoodRx, or a meditation app, you may be entering into a relationship with dozens of other companies. Even if you had time to go over privacy policies with a fine-toothed comb, you might never learn where your data ends up, or what it will be used for.

GoodRx users CR spoke with found that troubling.

“Machines can break, a human can make a mistake, and then it's all out there. It's happened before,” says Hanna, a GoodRx user who lives in New York, and does marketing work in the cosmetics industry. Hanna uses the app to check the prices for her birth control, as well as Lexapro, Trazodone, and Wellbutrin, drugs she takes every day for anxiety and depression.

But that won’t stop her, or other consumers we spoke with, from using GoodRx or similar apps. “The service they’re giving, with the state of our health insurance in this country is, like, necessary,” Hanna says. “My $300 medication is about $28 with GoodRx. I’ll take that. You know what I mean?”